Anatomy of a Phishing Attack VI

This one comes to me from a friend. Sometimes, everything looks right, yet something doesn’t feel right about the situation; it doesn’t pass the “smell test”. That’s the case here, where the friend asked if I’d also take a look. The cyber actors went a little further than usual, but once I dug deep enough, I found enough evidence to confirm our misgivings.

The Bait

The friend, like me, is seeking a new job. So, a text coming in with an offer to apply, followed by a job offer email, is pretty tempting.

In this case, cyber actors first compromised a website, copying its web pages as part of its infiltration. While I can’t tell what platform the original company uses to host their website, I feel that Collection | Data from Cloud Storage and Exfiltration | Exfiltration over Web Service describes this sufficiently. They then registered a new website with a similar name. (Resource Development | Acquire Infrastructure) and left a redirect URL on the original company’s home page (Impact | Defacement) to deflect people trying to confirm with the real company.

The Hook

The hook begins with an SMS text message offering the job immediately after sending the phishing email with the job offer. The cyber actor posed as the firm’s HR representative and used the text to make the email seem more legitimate. They also sent the friend to a Microsoft online form to assess their fit for the role.

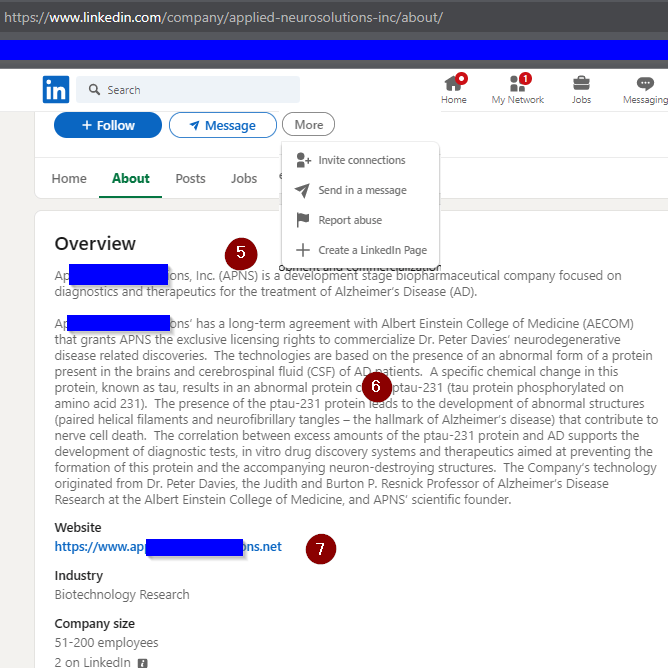

In addition to the copycat web domain, the cyber actors also either created a new LinkedIn profile or took over the company’s existing profile. In this profile, they had the HR representative and the copycat web address.

The Reel

The cyber actors were looking for personally identifiable information (PII) this time: The friend’s name, email address, resume, answers to likely interview questions.

Certainly, job scams exist to take direct advantage of job seekers by claiming an offer but asking for up-front money to secure the position. The FTC details several examples and how to report them. There is also a more recent trend.

The advent of remote work means that companies are looking all over for new applicants, not just local to the area. A person could be hired and work for years without physically meeting the other employees. This presents a big opportunity to cyber actors, who can already set up virtual private networks to appear to be connecting from a certain location, while really connecting from outside the country.

But to get hired, they need to appear to be a person in the country where the company resides. Thus, they take advantage of job seekers. The FBI’s original source can be found here; the PDF link is classified “TLP:White” meaning able to be distributed without restriction while following normal copyright rules.

The Catch

When a cyber actor sets up all this infrastructure, it brings more opportunities to report each particular item.

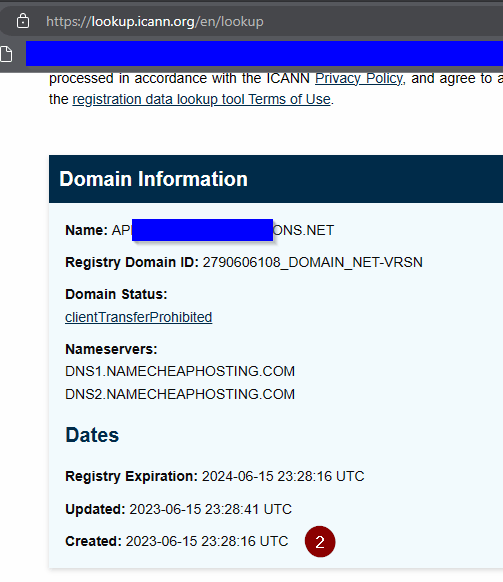

- ICANN’s WHOIS lookup shows the company who registered the domain and provides its abuse address.

- You can report any received emails and the fake website itself here.

- If you determine the real domain, you can contact them directly so they, as the brand owner, can also report the fake domain.

- In this case, the real domain’s compromised, so we’re not doing this yet.

- The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center is a good place to report, especially if they tried to set up a fraud payment in a contract, such as described in this article on Business Insider

- The LinkedIn company profile can be reported for abuse.

- The Microsoft form can be reported for abuse.

- You can block the number with your phone company and report it to the FCC.

Anatomy of the Attack

The SMS Text

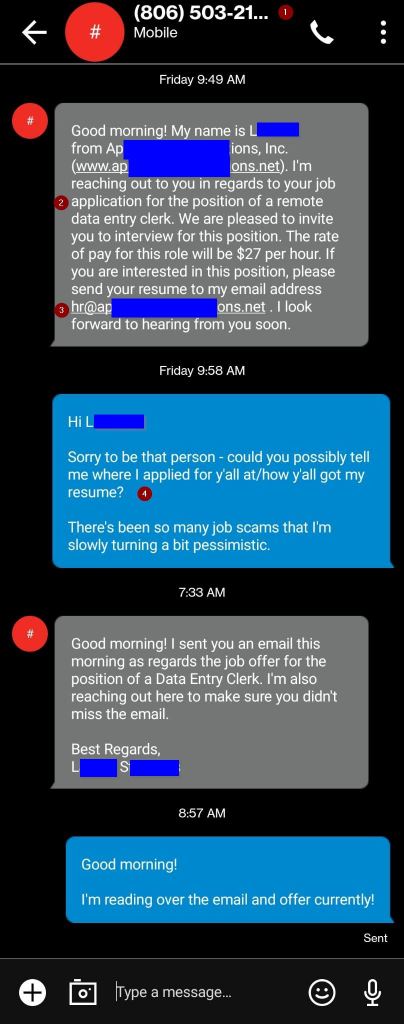

The SMS text is to the right, to take advantage of the long image.

- The unknown number is an 806 area code. An unknown number is sadly expected when we’re job hunting, so we can’t just discard these out of hand.

- I don’t know if they were aiming for a Texas zip code to target Texans, but we shouldn’t tell them that Amarillo is 600 miles from Houston with 4-5 area codes in between.

- Context clue – Cyber actors count on job seekers not knowing where their resumes have wound up, in order to be counted as one of the many places applied to thus far.

- They want you to email them first. Most email filters have a rule that says, if you email out first, then temporarily grant that address “permitted senders” status as we initiated the business relationship. With some email filters, this unlocks everything. Other, more granular email filters only prevent basic graylisting.

- This is a good thing – The friend did not offer any new information, but pressed on what the caller already knew.

Other clues that I didn’t number: The caller did not address my friend by name, but instead signed one of their texts. (Nobody signs texts like a letter.) Also, when my friend called the number to test it (and recorded the call in process), the number connected to an automatic voice mail, identifying itself only as “HR Line”. This is a standard trick – this allows the same number to be used in different scams with different companies.

The Email (Excerpt)

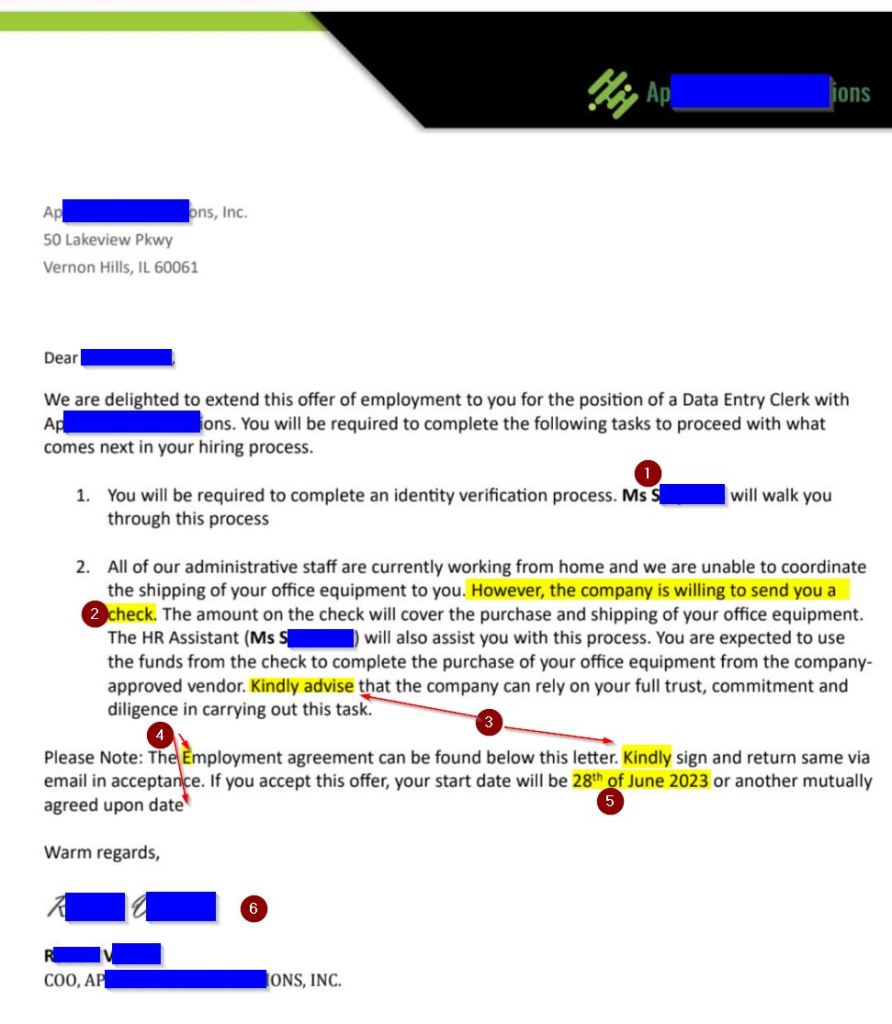

The email included a 4-page PDF, which appeared to be on company letterhead and included a job offer.

In addition to the concern of receiving an offer without a proper interview, here are some red flags one can see within the letter.

- Pretexting – Instead of “our HR department” or the like, the letter specifies the same person who texted. This pretext thus reinforces the idea that the text is legitimate.

- Here’s the fraud hook. They have a “company approved vendor” where you will have to “purchase” your equipment and then be “reimbursed” with a check. In reality, neither check nor equipment will arrive.

- Americans just don’t use “kindly”, but it’s the go-to word for anyone who learned English as a second language.

- The few grammar errors on this page amount to one errant capital letter and one missed period.

- The date format also hints at an out-of-US origin.

- The person named as COO exists in LinkedIn, but he does not have any experience with the named company. The name seemed unique enough to make it highly suspect there were two biotech executives with the same name.

The LinkedIn Profiles

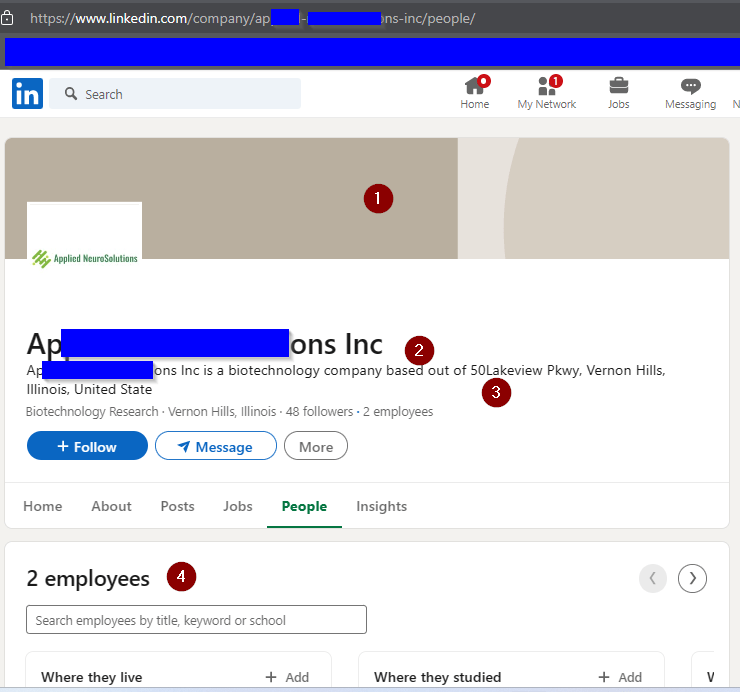

The company profile has several red flags to it.

- No cover photo. While many of us individuals still haven’t chosen a cover photo, it’s rare to see a company without one – their headquarters, a fleet vehicle, a pic of an employee doing something related to the company…

- Instead of a motto or press blurb about the company, it’s a statement of where they are located. Strange, since this is provided by LinkedIn right underneath.

- And they made an error on the address. Something as public as a LinkedIn profile would get quadruple-checked for errors, and any found would be removed immediately.

- Only two employees on LinkedIn? Maybe for a mom-and-pop, but for a biotech company that would be angling for venture capital?

- The overview offers a stock ticker for the company as APNS. This is not a stock ticker on any stock exchange covered by The Street.

- This seems rather detailed for an “overview”, and likely lifted from the real company’s webpage.

- The copycat domain here shows that whomever controls this also controls the copycat website.

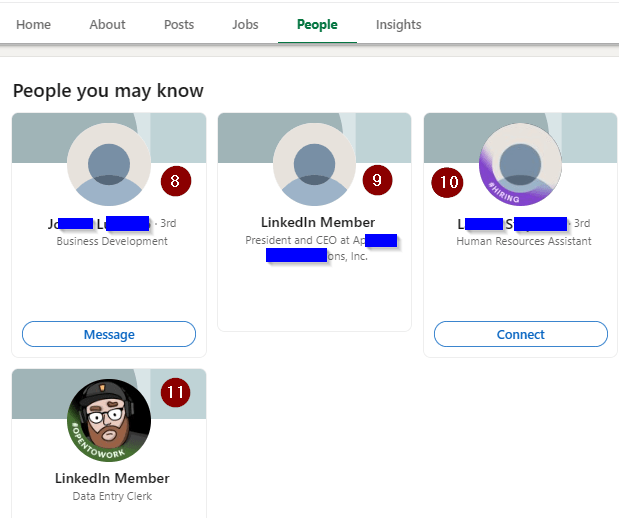

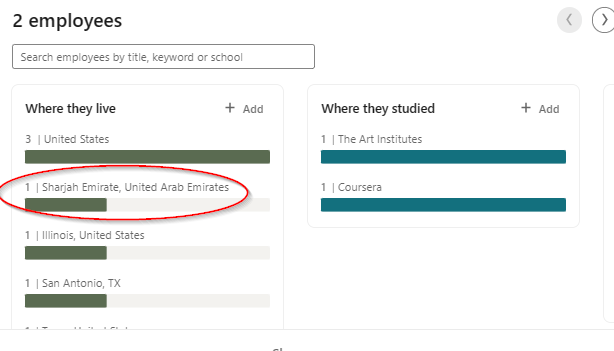

- Of the four people associated with the site, it’s interesting that none of them have real-life profile photos. PS: If you look on this person’s profile, you’ll find out their role at this company is also “Data Entry Clerk”, the offered position.

- Plausible deniability in blocking anyone from seeing the name of the “president and CEO”. (See also the bottom picture.)

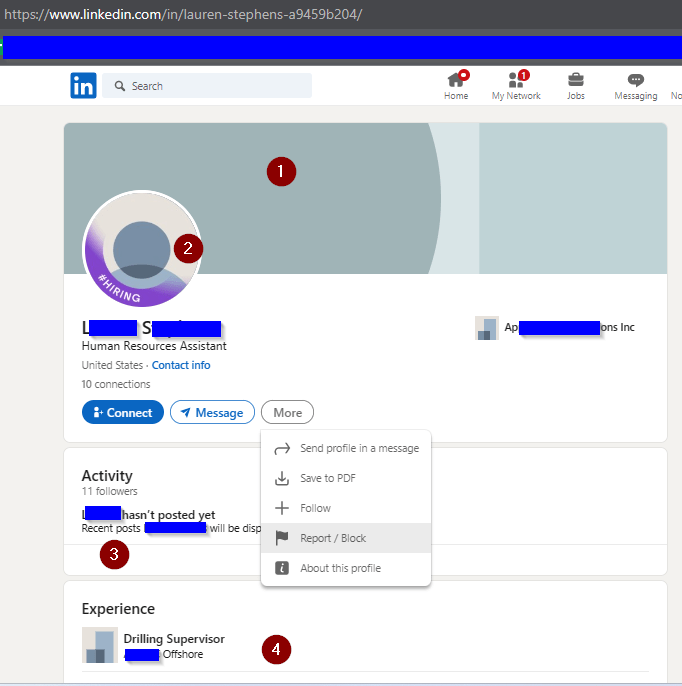

- The named HR person is there to again lend legitimacy to someone performing a casual search. But only an “HR Assistant”? And no other listed HR personnel?

- Another data entry clerk.

One More LinkedIn Profile

The LI profile of the “HR Assistant” has 1) no cover photo, 2) no profile photo, 3) no activity, and 4) only experience is an unrelated job. Not shown: The profile’s interests are in two UAE Sheikhs and 5 companies that all seem to fit the same clues as this one above.

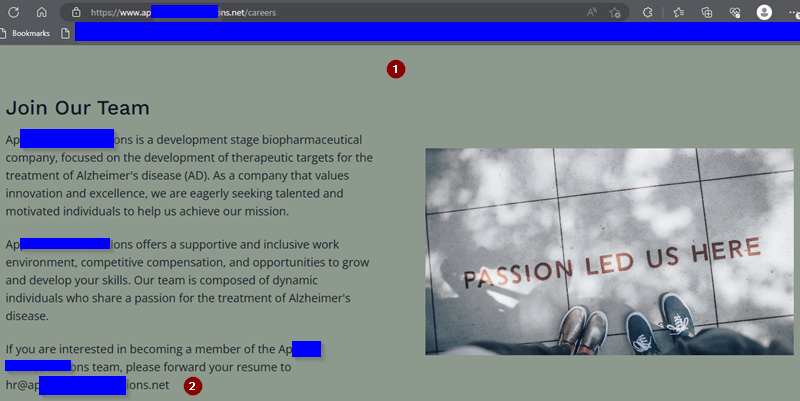

The Website

This copycat was pretty easy. The true website is a .com, and they did not buy the .net domain of the same name to prevent exactly this kind of thing from happening. With the proliferation of top level domains (the .com, .net, .edu, .blog, etc), trying to keep “my company name dot everything” can get really expensive, but most companies take advantage of registry companies’ deals for cheap or free domains to buy up some of the more popular variations.

On the far left is the fake website. There isn’t much to it, but what is there looks correct and professional. That hints at the cyber actors lifting the HTML right from the original website to use in their copy. (Thus, they’re a copycat.)

The only real flag is in the careers page. In an era where everyone uses a Taleo or Workday or other ERP tool, suggesting all resumes go to an email address feels wrong. Plus, when the main “contact us” is a webform so that you’re not OFFERING an email address to DDoS in the first place, listing an email address here betrays that message.

The middle image is from ICANN’s WHOIS lookup, which is an enormously useful tool to check out websites. It tells you when the domain name was purchased – only five days before this phishing attempt! But it also offers who the registrar is (Namecheap) and how to email them for abuse, and any identifying information about the site owner. A lot of this is hidden, but the addresses are often shown. What’s telling is that the address in this case is to a virtual office in Reykjavik, Iceland.

The far right image is what happened when I tried to go to the .com address. I have a separate device for testing links, and the anti-virus on that device flagged the redirection and the new site it was trying to take me to.

2 responses to “Fake Job Offer with a Copycat Domain”

[…] In my case, it’s more likely that they’d want to bring legitimacy to their webpage by being able to link a real person (me) to it, and along the way, they’d likely try to trick me into purchasing my own work supplies. […]

LikeLike

[…] In my case, it’s more likely that they’d want to bring legitimacy to their webpage by being able to link a real person (me) to it, and along the way, they’d likely try to trick me into purchasing my own work supplies. […]

LikeLike