Possible Fraud – Caveat Emptor!

Salesman: Science!

A Million Ways to Die in the West, 2014

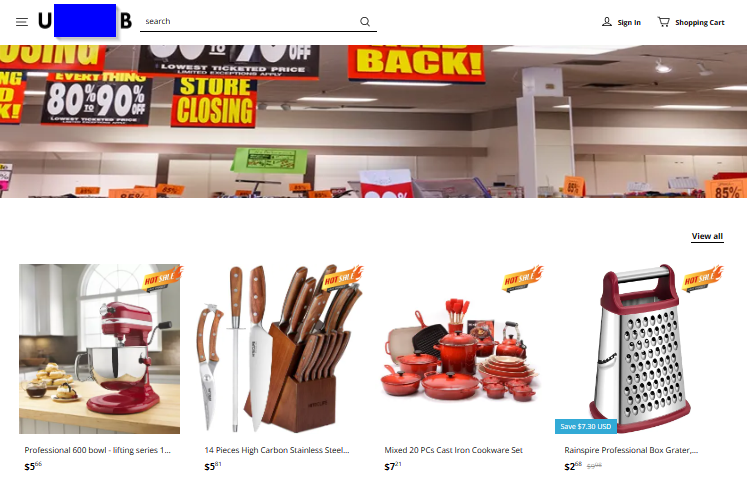

A family member sent me a link to check. It was a random set of 6 characters in the .shop domain, and the site advertised a lot of “final clearance” items at ridiculously reduced prices. I’d been getting similar ads in my social media feeds, so let’s check these out.

The cover of a site going out of business fits the “snake oil” merchant profile: Set up shop at one location (domain name), advertise and “sell product”, then shut down and move off to the next town (new domain name) before people test the product and find out it’s not real.

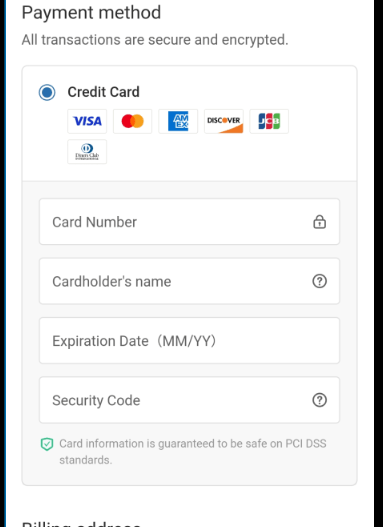

This isn’t a phishing attack per se. It’s a lot more direct. They’re after your money – specifically your credit card info. The fishing analogy still applies.

The Bait

I see these the most as sponsored ads on social media. “Going out of business sale!” “80%-90% off!” The associated images are typically high dollar items.

This speaks to our greed. Everybody loves free stuff! The idea of some internet startup failing and having to sell all its products at rock bottom prices seems to click as true in many folks’ heads.

The Hook

Depending on how greedy they are per transaction, they’re either after just a one-time transaction, or they intend to store your cc info to use later.

How would they use that later, you ask? That CVV code you supply allows a dishonest vendor to run your account number again and again on things that don’t use a card reader. And being able to set a different shipping address let’s them make purchases for themselves, but your bank only verifies (and sees) the billing address.

Why would they just do one transaction, you ask? Doing this allows them to play a longer con by delaying when people report them. The site typically warns you that they have to use a slow shipping method – 4 to 8 weeks or more. Will you even remember you purchased an item online by then? If you wait that long, they will have long since taken out the transaction money before you report an issue to your bank. You might still be compensated, but the bank is out that money.

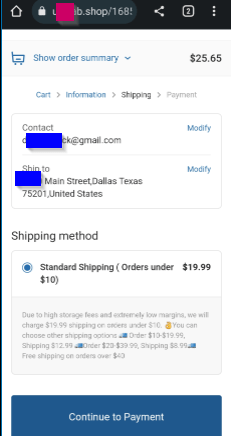

To help them get a larger payout, they will pad the price in shipping. Here is what this site shows – a $20 charge for under $10, $13 charge under $20, and a $9 charge under $40. “Free shipping over $40”, but they’re getting $40 or more out of you at this point.

The Reel

Once you have selected your really cheap items and gotten through the checkout, they present you with options. The fewer options, the more suspect the site. This site offers only a credit card option – no PayPal, no other methods.

The Catch

How do you protect yourself?

First, rely on that feeling of “this is too good to be true.” That’s your common sense talking. The bigger of a stretch an ad makes to make its pitch, the more likely it is that something is suspicious.

Anatomy of the Attack

1. Look for clues in the ad.

Here’s an example of an ad from my own feed. It’s more focused – the larger Lego sets are famously expensive, so finding a cheap way to get a complete box appeals to folks.

- Look at the profile name. Is it a brand you recognize? Also, companies are more likely to verify themselves on social media platforms.

- Within the tag line, look for “sponsored ad”. This separates the item from your other feed traffic.

- Look at the prices. If they are too good to be true, the company probably is fake.

- This particular button is “Apply now”. That is odd, as more companies like “Shop Now”. Maybe they created this as a “job”?

2. Investigate where it goes (without going there.)

Next, look at the URL (website) it takes you to. A lot will probably send you first through the platform again to count you as clicking through the link.

PS – the Lego link went to a single, hijacked page on a Lego reviewer’s legitimate blog. Buried there, it would be difficult to notice until the blog owner wondered why that one review page suddenly got more traffic.

Redirection links are good to lure you further or throw off basic web filters. And it might go through more than one hop to get to the final site. I use a redirection site to follow the chain and show me the site’s address.

Once I have that, it is off to the registrar to see how old the domain name is (that’s the last blah.blah between the // and the next / in the address. Most browsers now bold or highlight this for you.) Then I check to see if it’s on any real-time block lists (RBLs) on a site like VirusTotal. This only will give me clues if the site’s sending viruses or stealing user account into. Sites don’t get reported as much for straightforward fraud.

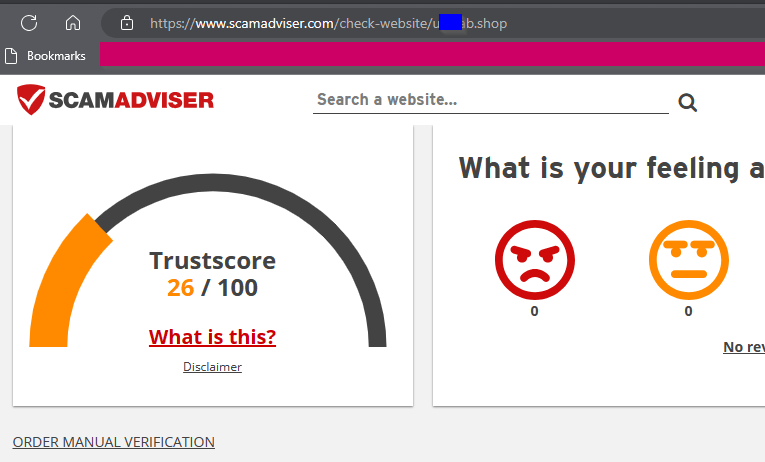

That’s the province of sites like the BBB and ScamAdviser. I found that scam advisor also pulls up the site’s registry info, which is good because different registrars are in charge of different top-level domains. (That is, .com , .net , .shop , etc.) The random-name site has only been active a few weeks.

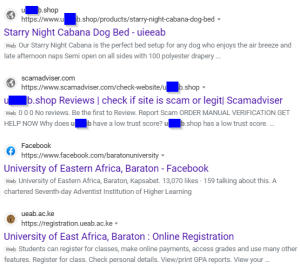

Another thing to look at is the site’s web presence. That is, do other sites talk about them? Do a search on the site name. This site only pulls the site itself and its ScamAdvisor report page before we get hits on similar words. (The university acronym shown here is close to, but different from the shop “name”.) No LinkedIn entry, no search engine business info page… this web presence is practically nonexistent.

3. If clear so far, cautiously look at the site.

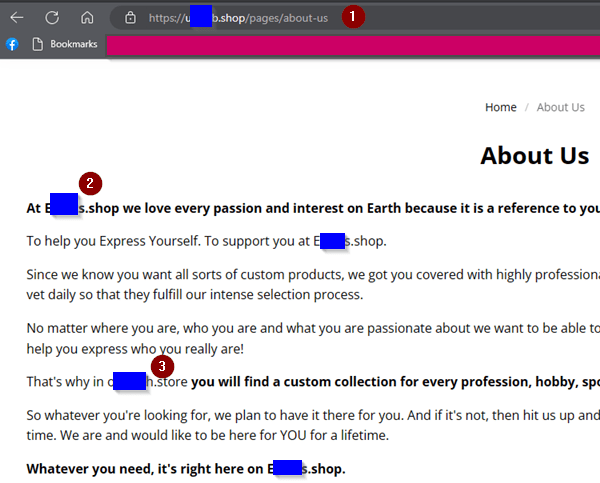

Say that something looks okay on all these. Look for clues on the site itself. Check out the menu for other areas than the shopping page. Does it have a business page? How about an “About Us”? Do they explain any random acronym within the domain name? The lack of these are clues that the site is suspect. This one’s “About Us” gives us more. Look how it refers itself to three different URL names! (First and last letters shown to show differences)

4. Report the site.

That registrar information is important for another reason: It will include an address where you can report abusive sites.

In the case of the rogue review page, I reached out to the blog owner to alert them of the rogue page. I also reported the ad to Facebook.

If you do think you’ve sent money to a fake shopping site, report it as soon as you can to your bank. Depending on when, they might be able to stop the transaction.

The FBI’s internet crime complaint center is another good resource. The FBI can assist more, in that their Recovery Asset Team can follow the transaction to the destination bank and put a hold before the cyber actors can take the money out of the account.

You must be logged in to post a comment.